Taking Derrida to church

I think I had might as well admit it. I'm a geek. And so when I got an email from Amazon a few weeks recommending me a book that ties together two of my passions, it wasn't long before I found myself clicking and ordering.

I think I had might as well admit it. I'm a geek. And so when I got an email from Amazon a few weeks recommending me a book that ties together two of my passions, it wasn't long before I found myself clicking and ordering.

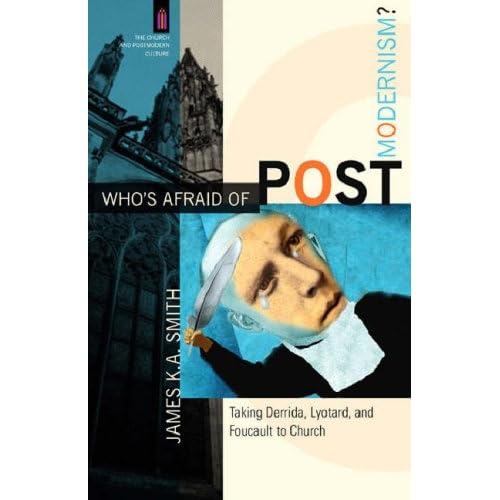

The book? Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? Taking Derrida, Lyotard and Foucault to Church. To some, these three French men won't mean very much at all. But to those who have studied social theory or social science at any level, they are recognisable as three of the most important postmodern French thinkers of the 20th Century. Much of the present postmodernist movement roots from their writings from the 1970s onwards. Derrida and Foucault, particularly, featured heavily in the syllabus of my Masters course that I undertook a few years ago in Bristol.

I always think that a good indication of how well you can understand something is shown in how clearly you are able to explain it. This book explains the theories (often made unnecessarily complex) admirably. The book includes references from films such as Memento, O Brother Where Art Thou and even The Little Mermaid to help the reader understand the philosophical challenges brought by the French trio. The author, James Smith, then seeks to think about how these writings impinge upon church life for evangelicals in the 21st Century.

The book has given me loads to think about, and I'm planning to share my thoughts on the chapters over the coming few weeks. In this post, I thought I'd start with the chapter on Jacques Derrida's writings (which I think was probably the strongest of the book) and Smith's understandings for the implications this has on church life.

Derrida in a nutshell

Derrida's writings focus on the central place of texts in mediating or understanding our experience of the world. By text, Derrida means something similar to 'worldview'. In other words, each of us has a necessarily filter through which we see things and the world appears to us. He's not doubting the reality of things we see, but shows that the way we see things varies depending on who we are and the position from which we see them. Derrida's best known slogan is 'There is nothing outside the text', but he later clarified more clearly what he meant, saying, 'There is nothing outside context.' As James Smith puts it, 'The context of both a phenomenon (whether a book, a cup or an event) and the interpreter function as conditions that determine just how a thing is seen or understood.' All this is very true: the way in which you diagnose a certain situation will depend upon several embodied circumstances that you possess - your period in history, your gender, your ethnicity, your socio-economic status and so on. We become wary of anyone who claims to know Truth - how can they possibly know the Truth when they only have a partial perspective on the world? (Derrida, like most people today, doesn't necessarily doubt the existence of Truth, but he would be suspicious of those who can objectively claim to know or tell it.)

The way in which Derrida's writings is most commonly experienced by Christians is probably in talking to non-Christians about the Bible. A Christian explains to a non-Christian something of the Bible's claims in a particular area. The non-Christian replies, 'Well, of course, that's just your interpretation of what it says. You can make the Bible say anything you want it to say.'

Taking Derrida to church

How should we respond to Derrida's writings. Interestingly, Smith makes a three suggestions.

- Fascinatingly, Smith suggests that the first thing that a Christian who takes Derrida's philosophy seriously will do is resonate with the Reformers' claim of sola Scriptura. If all events are subject to interpretation, informed by our own horizons, presuppositions and experiences, then we can say that there is no 'uninterpreted reality'. All people - Christians included - see the world through an interpretative framework or lens. Smith says that this frees us as Christians to lay our pre-suppositions on the table (for they are as valid as anyone else's), but 'also to ask ourselves whether the biblical text is truly what governs our seeing of the world'. He goes on, 'If the world is a text to be interpreted, then for the church the narrative of the Scriptures is what should govern our very perception of the world. We should see the world through the Word. [...] To say there is nothing outside the text, then, is to emphasise that there is not a single square inch of our experience of the world that should not be governed by God in the Scriptures. But do we really let the Text govern our seeing of the world?'

This is a very helpful observation. Like David, we need to realise that our understanding of the world can sometimes be clouded. We, too, need to see Scripture as 'a lamp to my feet and a light to my path' (Psalm 119:105). Scripture alone, through the power of the Spirit, can cut through our own pre-suppositions and those of the culture and society of which we are a part, and help us interpret the world as it really is. - Secondly, Smith says that Derrida's work will affect how we read the Bible. He calls for us to be honest. When we are charged with the fact that we might only interpret a text in a particular way, we need to admit that this is true. A case in point came for me in studying Romans 13 at church last Sunday on submitting to the authorities. It became immediately obvious that the fact that our Bible study group were all from democracies and historically situated after the regime of Nazi Germany affected our reading and interpretation of the text. The honest reply to the charge of is, then, 'Yes that could be true.'

Smith's answer to this problem is community. He exhorts community as the way of, together, combining people's contexts and together forming an interpretative framework. Practically, then, he says that the serious Bible scholar will not only read commentaries and interpretations of passages from other people like them, but will also want to hear what other voices of people not like us have to say on these passages. Smith would, then, have Western Bible scholars look to the global church to hear the interpretation, say, an African can bring to a text (it would certainly be interesting to hear they interpret Romans 13!). As Smith puts it, 'These other voices - so often marginalised by the Western church - are received as voices of the Spirit at work in our global brothers and sisters, illuminating us by illuminating them.' I guess that this is what the Global Christian Library series is attempting to do, providing inter-cultural exposition and application of the Christian faith.

However, Smith also wants to include historical voices in the interpretative community. As he puts it, ideally 'we recite the ecumenical and historic creeds because these are witness of our community past - the way for us to hear the interpretations of the ancient community, which was indwelt by the same Spirit that indwells us and grants illumination today. The pastor's preaching indicates a serious engagement with the early Church fathers and Reformers as co-interpreters. All of this helps us understand that the church is a community, a 'holy, catholic church', which has endured through millenia.' - Thirdly, Smith commends wide preaching of the Bible. In other words, in order to take the totality of the text of the Bible seriously, a church which is engaging with Derrida will not impoverish itself by staying in one part of the Bible alone. Rather it will be committed to a systematic teaching across all of Scripture, which, as Smith puts it, '... will guide us through the entirety of the Text's narrative, rather than leaving us to the private canons and pet texts of the pastor.'

Smith doesn't use this terminology, but Scripture itself then becomes the third 'interpretative layer'. Of course, without the other interpretative layers mentioned above, we are open to the charge of mis-interpretation. But the 'golden thread' of Scripture is a third vital layer (which I think is underplayed in the book) that helps us to be more sure that our interpretation of Bible passages is correct. As the Westminster Confession puts it, 'The infallible rule of the interpretation of scripture is the scripture itself; and therefore when there is a question about the true and full sense of any passage it must be searched out and understood by other places that speak more clearly.'

I find all of this very helpful. Smith's reading of Derrida makes us humble. We can admit that we do not understand all of Scripture, and that we need other voices and, above all, God's Holy Spirit to help us to understand it better. However, this needs to be balanced alongside the idea of 'spiralling into the Truth' - incomplete knowledge is not necessarily false knowledge.

So how would I now respond to the charge of, 'That's just your interpretation'? I think now I'd admit that, yes, it could be. But I'd then seek to show how orthodox views of theology are shared across history, across geography and across the Bible. Praise God that his truth is able to speak into all cultures and situations - praise God for Revelation 7:9: 'After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb.'

I'd be very interested to see what you make of this discussion, and will add my thoughts on Smith's chapters on the writings of Lyotard and Foucault in due course.

3 comments:

I found this post very interesting. I have never studied this sort of stuff but I always find it interesting and I think that there might be a lot of truth in it.

I like the point about community. It is very important to allow ourselves to hear another story, another 'text'.

Thinking about it, that is one of the reasons that I have enjoyed talking about penal subsitution with you and thebluefish. It is no good talking to people who have similar views to myself about something that other people believe. There, there is no real learning.

We learn more when we engage in conversation and debate with other views in a non-defensive and open way.

I remember studying Existentialism as part of my French degree at Lancaster University (although I didn't finish it). I remember finding it quite tough to be a Christian and to stand up for Christian beliefs. A friend of mine from home (Bristol) was telling me that he enjoyed reading about existentialism because he said it was basically everything we believe with God taken out, especially with reference to the almost inevitable depression that can come from it. God thus becomes the hope which changes everything for us and makes it worthwhile.

well how about that. we both swore against it, and we both caved.

I like this post, but I wonder if the sola scriptura route is incomplete without the personal nature of it - significance that in John's gospel we discover that both the Word and the Spirit are in fact eternal and personal, and speak to us. Here's the Don talking about the Yale School

George Lindbeck is constantly saying we need to have more of the bible in the churches, we need to teach the bible, we need the bible in our midst, we need to memorise the bible in our schools and churches, we need to hide the bible in our hearts, we need to rethink in terms of the bible, we need a repositioning of our imaginations in terms of biblical categories. YES! AMEN! Except that when you push George Lindbeck hard enough, what you can't find him saying (possibly he's hinting at it in his last 2 or 3 essays, he may be shifting), but what you can't find for the last 35 years in book after book and essay after essay, you can't find anything that has him admitting that these wonderful texts have any extra textual referentiality, that is to say that they refer outside themselves to things. In other words, these texts are supposed to shape our imaginations, but we cannot say that they say something true about God, we cannot say that they say something true about Jesus. We dont know that, you see Lindbeck is too postmodern to be able to say that. What he is saying instead is that if we are christians, we must allow those texts to shape our minds and all of that, but we cannot say that what those texts say is objectively true and refers to something outside themselves that's true. Beware of that position, because it leads ultimately to meaning that you are renewed by thinking about what the bible is talking about, whether or not what the bible is talking about is true.

...If all you've got that saves you is the reformation of your mind by reading and re-reading the bible, it's not Christ that saves you, it's the ideas that save you. You've only gone back as far as scripture. You've not gone back to what scripture actually refers to outside itself. You have no extratextual referentiality. That is idolatry. It's Bibliolatry.

that's my worry. I've been thinking bout this a lot recently so I think I'll post on it. It's basically along the lines of a theistic/pantheistic/agnostic/atheistic view of texts.

ps you're creeping up my geek top ten too.

Hi Chris,

I only just noticed your post on this so sorry not to have got back on this before. I think I see what you're saying but I'm not sure that's either what me or James Smith would be commending. Of course, there certainly is a personal dimension to Scripture reading; however, however even this comes with an interpretative framework. I don't think this is driving towards an overly cerebral emphasis on Bible reading, but a humility that says that certain cultures or periods of history can be blind to what the Spirit is saying to them.

What do you think?

Post a Comment