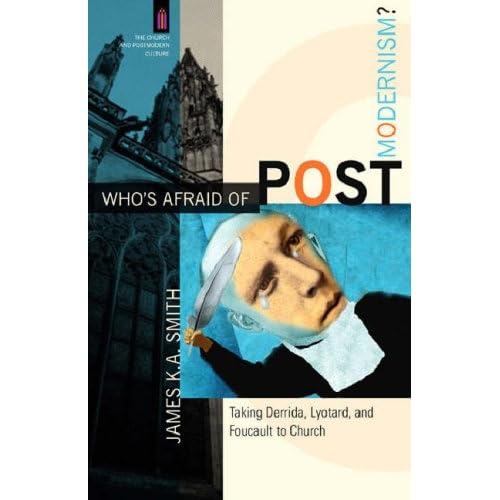

In a couple of previous postings (here and here) I started a mini series reviewing James Smith's book Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? Taking Derrida, Lyotard and Foucault to Church. This final entry examines what Smith has to say about the writings of Michel Foucault.

In a couple of previous postings (here and here) I started a mini series reviewing James Smith's book Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? Taking Derrida, Lyotard and Foucault to Church. This final entry examines what Smith has to say about the writings of Michel Foucault.

Of the three cultural theorists in questions, it's perhaps Foucault whose work I am most familiar with. As someone who was a geography undergraduate, Foucault's work is more overtly spatial than much other sociological writing (see, for instance, in his work on prisons in Discipline and Punish). In particular, his methodology - known as 'archaeology' - where he traces through how a particular thing or phenomenon has been viewed through different historical epochs, is something that has been enthusiastically embraced by many social sciences.

I guess the other thing to add is that, in some ways, I've never felt quite so concerned about the ramifications of Foucault's work to my Christian belief. Sure, there were challenges as an undergraduate - particularly in being told that Biblical condemnation of certain practices reflected only the culture it was written in (rather than wrong for all humans in all places in all periods of history). This argument leads to a kind of moral relativism, which is obviously incompatible with a Biblical worldview. But, overall, I'd always felt more resourced to tackle some of these ideas head on than the more subtle arguments coming through language and semiotics.

Anyhow, in his book, James Smith tackles the subject of discipline, which is familiar in many of Foucault's writings. Foucault argued that society and institutions are designed to give vision to certain people, forcing others to behave in certain ways. Foucault's famous example is Jeremy Bentham's 'panopticon' prison design, whereby the prisoner cannot see any other fellow prisoner, and yet knows that the eyes of the prison guard could be upon them at any one time. Britain's obsession with CCTV is perhaps the same - we change our behaviour because we know that at any given time, we could be being watched. This is the very idea of surveillance.

It's within this framework that Foucault assembles his theories of knowledge. Foucault throws out the idea that truth is somehow innocent - instead, certain ideas and biases and prejudices are combined in order to control others as we would like. Like the architecture of the panopticon, Foucault claims that we assemble ideas as 'truth' in order to make people behave in a certain way. And so we come to Foucault's famous slogan - 'power is knowledge' - as Smith puts it, 'at the root of our most cherished and central institutions ... is a network of power relations.' Power and knowledge are inextricably linked, in order to make people conform in certain behaviours.

And so, linked to this is the idea of a deep 'hermeneutic of suspicion' - we can now consider no truth to be innocent. As Smith puts it, 'what might be claimed as obvious or self-evident is, in fact, covertly motivated by other interests - the interest of power.' And so different historical eras have had different 'truths' because certain people have wanted to have power over others in some way. Foucault's picture of society is a disturbing one - one of control and domination - and his message rings through: be suspicious of all.

Taking Foucault to church

Smith's main contribution here is a reflection on the nature of power. In the main part, he is happy to go along with Foucault's description of society and its institutions, and the web of power relations within. But he is unhappy to take the negative Foucauldian of power. This longer quote is, I think, helpful:

Should we accept this negative view of power? Is power all bad? Specifically, can Christians share in this devaluation of power and discipline as inherently evil? Can we who claim to be disciples - who are called and predestined to be conformed to the likeness of the Son (Romans 8:29) - be opposed to discipline and formation as such? Can we who are called to be subject to the Lord of life really agree with the liberal Enlightenment notion of the autonomous self? Are we not above all called to subject ourselves to the Domine and conform to his image? Of course, we are called not to conform to the patterns of 'this world' (Romans 12:2) or to our previous evil desires (1 Peter 1:14), but that is a call not to nonconformity as such but rather to an alternative conformity through a counterformation in Christ, a transformation and renewal directed toward conformity to his image. In fact, by appropriating the Enlightenment notion of negative freedom and participating in its nonconformist resistance to discipline (and hence a resistance to the classical spiritual disciplines), Christians are being conformed to the patterns of this world (contra Romans 12:2).

This seems, to me, to be a wonderful insight. Another sentence from Smith, 'what constitutes the proper end, or telos, of human formation depends on the ultimate story we tell of what human beings are and what they are called to be.' In other words, Christians must absolutely refute the view that power is all bad: the Spirit's power at work in us, for instance, is wonderful - he frees us from our sin and makes us more like Jesus, the perfect human being and the only one since Adam to experience living as humans were created to live (ie in perfect relationship with God). Power is positive if it is used for positive ends - and living the life we were created to live is the greatest of these.

Smith makes a couple suggestions for how Foucault's work ought to work itself out in the world. Firstly, we the church should recognise the process of disciplinary formation in society - unveiled we can be aware of those processes that would make us behave as those with power want (particularly to be capitalist animals) and then diagnose the correct Christian response. We need to realise that this process runs counter to what it means to follow Jesus as a disciple.

Smith then says that we must come up with our own disciplines 'that will counteract the formation of MTV and television commercials'. Smith goes on that 'we would do well to recover the tradition of spiritual disciplines such as prayer and fasting, meditation, simplicity and so on as a means of shaping our souls through the rituals of the body.' I guess this is where I think James Smith sells himself a bit short. He's right in quoting Romans 12:2 ... but spiritual disciplines themselves cannot transform. What is needed is to 'be transformed by the renewal of your mind' (ESV). Smith does speak about the need for grace to change - but this comes powerfully through the work of the Spirit as he transforms us by the Word. The greatest way of being transformed in a culture which screams out anything but Jesus is Lord is the Spirit's transforming power through the Word.

In particular, it would seem to me that teaching on God's design for humans is going to be necessary if we are to crave the Spirit's power in transforming us to be like Jesus. I remember the first time when someone told me that Jesus was the only person who has ever lived who was truly human. Jesus is the only one who lived as he was created. A Christian view of freedom (the view of John 8:31-32) that we are free when we live as we were created (rather than the more 'democratic' view of choosing A or B) will be vital. Christians and non-Christians alike need to see the beauty in God's blueprint for humanity in order to want the Spirit's power for change.

A couple of final things

In closing, I want to add a couple of points. Firstly, as I hope you've seen, I've tried to give an accurate and fair review of this book. I think, overall, it's a great and helpful read. However, the book's reviewers (on the back cover) are nearly all emerging church leaders, including Brian McLaren, Robert Webber and Carl Raschke. Why is it that the emerging church seems so happy to engage with the postmodern mindset, where others - which I think are often set upon more Scriptural convictions - seem slow to do so? Must we choose between a grouping of churches that probably unhelpfully panders to the postmodern mindset and between the rest that seem completely unwilling to do so at all? (Or is that a caricature?)

To finish, I want to draw attention to something that James Smith doesn't examine at all, and that's addressing Foucault's hermeneutic of suspicion. I remember giving a talk about a year ago at the height of the Da Vinci Code hype: now there's a postmodern idea - 'trust no-one!' In this talk, I addressed the natural suspicion that we have of truth - 'why do they want me to believe this?!' It seems to me that the way in which we counter the suspicion that people have of the gospel is authenticity - to share our lives with others. I remember asking those present in the talk to question the motives of the Christians that brought them - 'Why do you think they want you to become a Christian?' Christian authenticity - sharing our lives as well as the gospel - is a key way in which we can demonstrate that we are not trying to have power over others, but that we long for them to come to the truth, because we love them and long for Jesus' glory. Now there's two motives that in eternity won't be questioned.

A few weeks ago I read John Carlin's excellent book Playing the Enemy. It tells the story of Nelson Mandela's project of nation building in post-apartheid South Africa, climaxing with the 1995 Rugby World Cup final.

A few weeks ago I read John Carlin's excellent book Playing the Enemy. It tells the story of Nelson Mandela's project of nation building in post-apartheid South Africa, climaxing with the 1995 Rugby World Cup final.

Just got back from holiday in the early hours of the morning - had a wonderful time in Turkey, good rest and relaxation in a country that I had no idea was so beautiful.

Just got back from holiday in the early hours of the morning - had a wonderful time in Turkey, good rest and relaxation in a country that I had no idea was so beautiful.